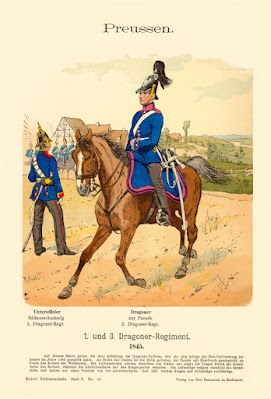

Knotel print of a Prussian Dragoon in 1845 sporting the 1811 cavalry saber, the standard weapon for all Prussian non-cuirassier cavalry regiments from the 1820s until 1852.

Based on the interest shown in the mention of my recent acquisition of an Austrian M1861 sword in the last post, I thought I'd meander into a hobby-adjacent interest of mine: antique swords. As part of my ongoing efforts to organize things, I am putting together a portfolio with images, descriptions, points of inspection, provenance, and history of my swords. It's something I should have been doing, really, as I acquired each, but the same goes for lots of things (like exercising regularly). Of course, I'm not tackling this task chronologically, by nation, or in any other systematic way. No, I'm doing this organizing in a typically unorganized manner, as the organizational butterfly flits and time allows. As I complete the listing for each, I'll be sharing (inflicting?) this "sword lore" on you, dear reader, in this blog. So you've been warned. In this post, we'll be dealing with the first artifact, my 1811 Prussian Cavalry saber. And now, for those few who have the spare time and stomach to still be reading, you may, as usual, clix pix for BIG PIX in this blog post...

1811 "Blucher" Prussian Cavalry Saber

Above is the subject sword from my collection, the famous (among sword followers) "Blucher" cavalry saber. It, like most of my swords, is an authentic service (ie trooper's) weapon. The blade is roughly 32" long and as you can see, it is very much a curved, cutting weapon. Although it can be used "at the point" to thrust, that is not the primary employment. During the Napoleonic wars, this distinction between cut and thrust, corresponding to light and heavy cavalry, respectively, was still very pronounced. As the century progressed, these two designs would merge into a universal pattern for all cavalry (but that is the subject of another post for another time). For now, we'll stick with the subject weapon. For starters, we do have to talk about the genesis of this sword during the Napoleonic wars.

After the disaster at Jena in 1806, Prussia would suffer occupation until well after 1812, when it would it rise up in the Befreiungskriege and join the Sixth Coalition against France. In order to mobilize for war, Prussia had to greatly expand and equip her army. Although manpower was available, materiel and the means of production were limited, to say the least, and portions of the country still had to liberated. As the above image illustrates, many units of the newly expanded Prussian army (and even some still in the 1815 campaign) donned interim gray uniforms until regular uniform production could get going. Other support came from allies, most notably Britain. Perhaps the most visible and well known form of British support came in the form of the pictured Portuguese pattern uniforms and shakos that many of the newly raised Prussian regiments donned. Anyone who has ever put together an 1813 Prussian army knows of these.

Probably less well known, however, is that the British equipped the Prussian cavalry (except for the cuirassiers) with the British 1796 Light Cavalry Saber. Above, my British 1796 Light Cavalry Saber next to my Prussian 1811 "Blucher" Cavalry saber: notice anything?

Depictions of Prussian Napoleonic cavalry above--one contemporary (Funcken) and one period--with the British 1796 Light Cavalry saber. The British 1796 Light Cavalry saber is a classic (and will be the subject of another post). Suffice it to say that the Prussians recognized the virtues of this weapon, and when it came time to produce their own, they modelled it on the British 1796. The resulting saber, the Prussian 1811 Blucher, is a sturdier, more robust version of its more slight British cousin (sort of like German cuisine). It is unknown, exactly, when the sword acquired its unofficial "Blucher" nickname, but it is assumed to be in connection with its genesis in the Napoleonic wars. Given the state of affairs in Prussia, however, few 1811 Bluchers were actually produced before the fall of Napoleon. Any that were would have been issued on a "low density" basis (ie to Prussian staff, couriers, etc).

As for the Prussian cavalry, they would continue to carry the British 1796 Light Cavalry saber that they were already equipped with through the 1815 campaign and beyond. Although you may see these swords (misleadingly or unknowingly) advertised as "Napoleonic" they were not produced in numbers until the 1820s, and the Prussian cavalry probably were not fully equipped with them until the major reorganization of the 1830s. Having covered its background, it's now time to take a look at the sword.

Markings

Although all swords tell a story, the marking system on Prussian swords of this era provide a particularly rich and engaging one. Both the swords and the scabbards have their own stories.

Ordnance Marks

The small letter and crown stamped on the backstrap and lower guard on the hilt of this sword are government proof marks: the equivalent of a "US" stamped on US Army hardware.

Unit History

Like any other piece of equipment, swords were recycled, rebuilt, and reissued, as were scabbards, and had many lives. Although this is often a hidden history, Prussian swords and scabbards recorded theirs. When the 1811 was superceded for use by the cavalry, it was cascaded to the artillery, then to support units, and then to reserve and other units. Upon receipt, the armorer would put the unit stamps on the langet (above left) and on the scabbard (above right). The previous unit stamps would be struck through. When collecting swords, it is not unusual to have a scabbard that does not match the hilt, as is the case here (the paired items were separated somewhere along the line, and in the case of this item, this scabbard and hilt may have been later married in depot but left in stores and never reissued, hence not re-stamped). Here are the unit histories of this sword (hilt) and this scabbard:

Hilt: R.P.C 4. 42

Reserve Proviant Colonne 4, Weapon 42

Reserve Provision Column 4, Weapon 42

Scabbard: R.P.C. 7. 44

Reserve Proviant Colonne 7, Weapon 44

Reserve Provision column 7, Weapon 44

Previous Unit:

Reserve Lazarret 12, Weapon 5

Reserve Field Hospital 12, Weapon 5

Depot Marks

As with the unit history, the marks on the hilt cross guard and the scabbard ring tell a story of their own. These are depot marks and indicate that the item was repaired or rebuilt, and where. The convention is for there to be a number, followed by a letter, and possibly followed by another number. The first number is the weapon or inventory number; the letter indicates the depot. And if there is a number after the letter, it indicates the series (some sources suggest that this is "thousands"). Here is the depot/rebuild history of the scabbard and hilt.

Scabbard Ring: 345 S 3

Item #345, Spandau Depot, Series 3

(alternately, Item #3,345, Spandau Depot)

Hilt (Cross Guard): M 33

Item #33, Munster Depot, Series 1

(alternately, Item #33, Munster Depot)

This is a non standard mark, but an expert reached on a forum deciphered the absence of numbers in front of the depot letter to indicate a first series item (ie, a very early inventory item)

Blade

Blade

In the interest of brevity, I won't go into the evolution and conventions of Prussian blade markings. Suffice it to say that with time, particularly after 1831, they became more standardized and informative, including various forms of date, manufacturer, and a royal cipher or crown. Early blades, pre-1830, tend to have no markings or only a depot number. Given that the numbers on the spine of this blade do not conform to any of the post-1830 conventions, it is unlikely that they indicate a date (1833), and given that these are the only marks, it is likely that it is an early, pre-1830, blade. Even more telling is that the numbers on the blade match the depot numbers on the hilt (M 33), reinforcing the idea that these are depot marks, which in turn reinforces the idea that this is an early blade. As such, it is likely that this hilt and blade were put together--making "sword" #33, series 1--at the Munster Depot as a rebuild.

Later History

The 1811 Blucher Saber would be carried into combat by the cavalry for the last time in 1848 (during the First Schleswig Holstein War), after which it was decided that more hand protection was needed, leading to the design and adoption of the 1852 light cavalry saber (pictured above: of which I have an both a service and officer's version--reported on in another post). As has been mentioned, however, this was far from the end of the 1811 Blucher's service life. It was then given to the artillery and horse artillery. Eventually, a lighter version of the Blucher was designed for the artillery. Then the original 1811 Blucher sabers continued to serve, being passed to train and supply units, and then to reserve units, and then to administrative units and personnel, continuing in use through World War One.

A German Landstrum administrative and security detachment in World War One equipped with the venerable 1811 Blucher Cavalry saber.

Excelsior!

Fascinating sword study. I really don’t need another hobby, do I?

ReplyDeleteFunny, I didn't set out to "collect" swords, but over the years, picking up one here and there has turned into a collection (albeit a small one), and also a hobby. Sort of like getting old: it sneaks up on you.

DeleteExcellent info there Ed:).

ReplyDeleteThanks, Steve. It was a good exercise for me to get all this down. Glad if others find it interesting.

DeleteAnd that's a history!

ReplyDeleteThan you sir!

Warm regards

Thanks, Michael--given the marking systems, these Prussian swords do have lots to research and talk about (there's always a bit of conjecture, but I think I've got most of it right).

DeleteInteresting stuff Ed, do you have room to have your sword collection on display at home?

ReplyDeleteYes, Keith. I actually built a sword rack to hold them. At the time, I made it so that there would be one space for each sword, with one left over to spare--thinking that I was done acquiring swords. Now, of course, I'm having to double up on a few spots (ain't that always the way).

DeleteGood article, I found it interesting. Didn't realise a blade would be kept for so long.

ReplyDeleteHello, Stuart, That was one of the things that struck me as I started finding out about service swords (and it's not just the Prussians). Even more surprising (to me) than the blades was that they kept equal track of the hilts and kept re-using them as well.

DeleteSword Lore sounds like a good title for a series on netflix.

ReplyDeleteI liked the close up pics, and now I know more about swords than I did before. 😁

I'll have my People talk to Netflix's People; watch for Series One soon...or just keep an eye on this blog for when I get around to another posting.

DeleteInteresting and informative post, I didn't realise the longevity of these weapons, I have handled a 1796 light dragoon sabre, a work colleague's husband is a collector, he was delighted as he'd just got a Napoleonic French cuirassier sword, his are all stuffed into a corner of a study overflowing with history books, made me happier that at least all mine are on shelves!

ReplyDeleteBest Iain caveadsum1471

My few swords were also stuffed into a corner until recently. Good to see that's how others got started as well (also have the French cuirassier sword: another classic).

DeleteAn excellent post Ed…

ReplyDeleteIt’s nice to find out these little snippets about the life of an object.

All the best. Aly

Thanks, Aly. Aside from handling them, it's "reading" the story of each object that draws one into collecting, at least for me.

DeleteWhat a ripper post Ed. The word langet has now entered my vocabulary (hopefully it won't slip out the other side of my brain!).

ReplyDeleteRegards, James

We aim to inform and delight, James. Glad you found something to take along--in a future post, I'll see if I can work in "quillon."

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteVery interest and informative post. You may be interested to know that the men in the group photo are former kuirassiers "ehemalige" meaning former. The white tunics or "koller" have braiding up the front known as "kolletborte" or tunic border, indicative of kuirassiers. They probably have a great deal to be miserable about which would have included, "where is my straight bladed kuirassier sabre I used to have, sigh.

ReplyDeleteHi Lexi. Thanks for adding this note. I had noted that they were "former" cuirassiers. I also shared your thoughts about what it used to mean to be a cuirassier vs what these fellows had been relegated to, despite still wearing the proud white kollet. I think losing their palasches was probably the final insult!

DeleteMaybe they wore helmets, assuming they were even issued, as a consolation prize.

DeleteVery useful information! I have the chance to work with a Prussian "Blucher" at my job and saw what looks to be "I.M.M. 2 38" or possible "I.M. IV 2 38" stamped on the langet...on a sword proven to have been found by a local Confederate family at an major American Civil War battle site immediately after the war. Is there any place to look for guides to Prussian unit markings on their weapons? Would be good to have for future reference.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

DeleteOn page 27 of my reference, there is an example of a weapon marking that corresponds you your second one: That one is "I. M. VII. 3. 50." which is: "3. Infantrie Munitions Kolonne of Field Artillerie Regt Nr 7, Weapon 50." Following this example, I would say that the markings on your weapon would translate (in english) to "2nd Infantry Munition Column of Field Artillery Regiment 4, Weapon Number 38." I think that is a pretty safe assertion for its origins. Can't speak to it's life, post production, and how it wound up in the US or whether it was carried in action during the ACW. As far as the reference, it is a small form pamphlet: "A Compendium of British and German Regimental Markings Compiled and Edited By Gordon Hughes and Chris Fox" Printed by the Benedict Press, Lowther Road, Brighton UK, 1975.

DeleteYou might also try searching for publications by Gordon Hughes under "Gordon A. Hughes Publications, Brighton, Sussex England."

Delete